Adaptation Strategy: Coastal Wetlands

Coastal wetlands represent ecosystems that are permanently or seasonally inundated with either fresh, brackish, or saline water that is usually less than 6 feet in depth at low tide. 8 9 There are different types of coastal wetlands: salt marshes, fresh marshes, mangroves, and sea/eel grasses. In the United States, coastal wetlands cover about 40 million acres and makeup 38 percent of the total wetland acreage.1 The ecosystem services provided by coastal wetlands are essential to people and the environment. Services that are provided can include flood protection, erosion control, habitat and, fisheries preservation, water quality abatement, recreation, and carbon sequestration.2

How it works

Types of coastal wetlands

- Tidal salt marshes are usually found in areas where the accumulation of sediment occurs at the same or higher rate than land subsidence. They are important for supporting the spawning and feeding of several marine organisms. Hence, they represent a critical interface between the land and sea.

- Mangroves swamps are estimated to occupy between 16 and 18 million hectares of coastal areas globally. In tropical and subtropical areas, mangrove swamps replace salt marshes. In some instances, both mangrove swamps and salt marshes exist together.

- Tidal freshwater marshes are located close to tidal zones, but out of the reach of oceanic salt water. They comprise several features including salt marshes and freshwater marshes. Tidal freshwater marshes possess similar structural and functional characteristics as salt marshes. However, tidal freshwater marshes are more diverse because of reduced salt stress.

- Riparian wetlands are ecotones or interfaces that exist between aquatic and upland ecosystems. They possess distinctive vegetative and soil characteristics. Riparian wetlands are difficult to distinguish from surrounding landscapes therefore they are classified as mosaics of landforms and communities within a larger landscape. 10

Benefits

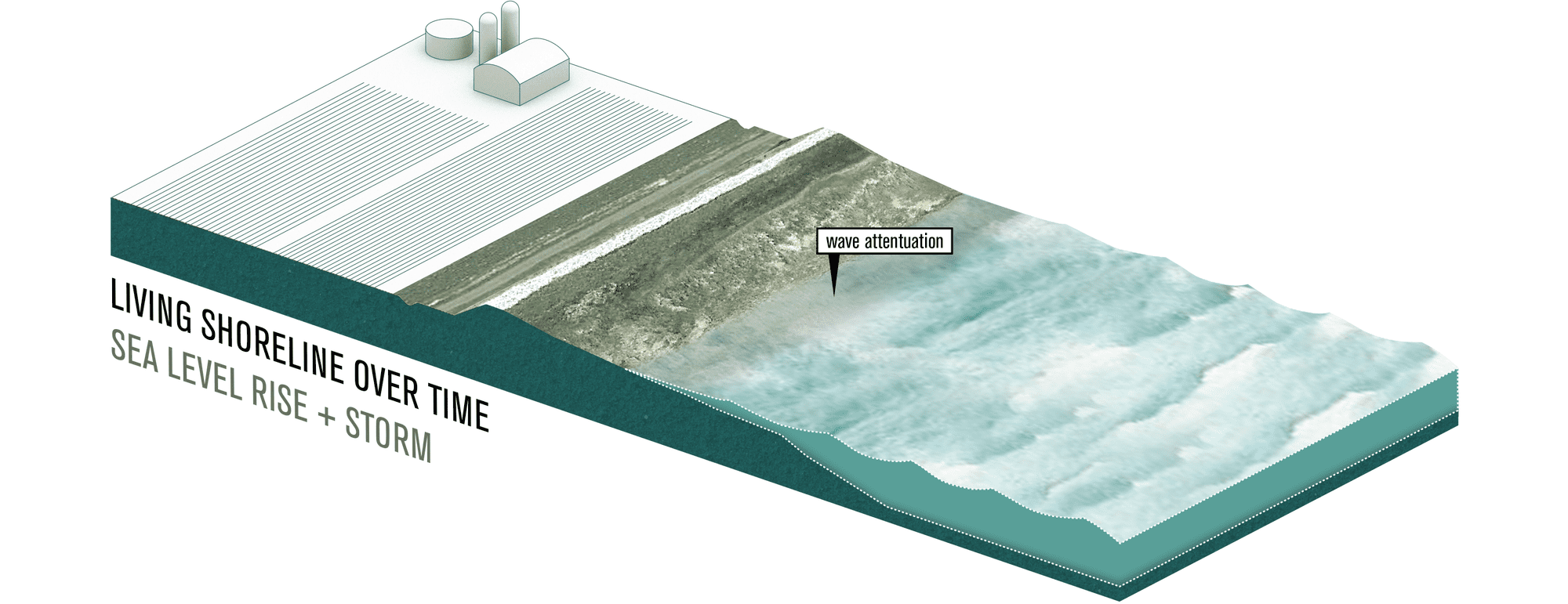

- Protect upland areas from sea level rise, and storm surges by buffering wave action.

- Reduces the frequency and intensity of floods by buffering and storing a significant amount of floodwater.

- Provides habitat for threatened and endangered species.

- Serves as a water filter for chemicals and sediments before they enter coastal waters.

- Sequesters carbon in salt marshes and mangroves. 11

Challenges

- Lack of integrated understanding of coastal ecosystems. Wetlands represent complex ecosystem interactions and understanding the interactions between these subsystems is still evolving.

- Transference of knowledge to practice is stymied by conflicts between coastal interests. 12

- Development pressures for residential and commercial space could lead to the loss of wetlands endangered species.

- Habitat degradation from chemicals and sediments due to land-use change inland. 13

Example projects

Bluebelt Program

Staten Island NY, USA

Bluebelt is a cost-effective and ecologically sound drainage system that captures runoff from streets and sidewalks. The program is designed to protect and enhance natural drainage channels, e.g., stream, ponds, and wetland to convey, store or filter runoff from precipitation and stormwater. 8 3 The design and construction of the Bluebelt began in the 1980s when the septic system in Staten Island was failing. During that time, planners recognized the importance of storm management and began acquiring land (wetlands, streams, and ponds) for the Bluebelt program.4 Since the 1980s, several watersheds were reclaimed and the Bluebelt has expanded greatly while improving the drinking water of the City.5

New Brighton Park Shoreline Restoration

Vancouver BC, Canada

The New Brighton Park Shoreline Restoration is a collaborative project between the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, and first nation groups to implement a design that supports the Park Board’s Strategic Plan, Rewilding Action Plan, and the Biodiversity Strategy.6 The project features a constructed tidal wetland that provides habitat for juvenile salmon as they migrate along the Burrard Inlet. The wetland also enhances the ecological function of the site by providing a resting and feeding habitat for shorebirds.7 The project is an excellent example of how a small-scale project can be a positive benefit to the overall ecological function of a site.

Citations

-

1.

↑

“Coastal Wetlands.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 1 Mar. 2019, https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/coastal-wetlands#whatAre.

-

2.

↑

Ibid.

-

3.

↑

“The Staten Island Bluebelt Expands Again.” Freshkills Park, 11 Sept. 2017, https://freshkillspark.org/blog/staten-island-bluebelt-expands-again.

-

4.

↑

Ibid.

-

5.

↑

Ibid.

-

6.

↑

“New Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Project.” Port of Vancouver, 4 Oct. 2018, https://www.portvancouver.com/development-and-permits/development/new-brighton-park-shoreline-habitat-restoration-project/.

-

7.

↑

Ibid.

-

8.

↑

In TeGrate. (nd). Coastal processes, hazards and society. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth107/node/1029

-

9.

↑

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/coastal-wetland

-

10.

↑

CHAPTER 4 Coastal wetlands: function and role in reducing impact of land-based management G.L. Bruland Natural Resources and Environmental Management Department, University of Hawaii Ma¯noa, USA. https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/brulandg/publications/CWM_Chapter04.pdf

-

11.

↑

https://climatechange.ucdavis.edu/climate-change-definitions/coastal-wetlands/

-

12.

↑

Canadian Science Publishing. 2018. Coastal wetland loss, consequences, and challenges for restoration. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/full/10.1139/anc-2017-0001

-

13.

↑

NOAA. (nd). Coastal wetlands, too valuable to lose. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/habitat-conservation/coastal-wetlands-too-valuable-lose

-

i1.

↑

NYC Department of Design and Construction. Bluebelt Wetland. https://freshkillspark.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/DIFk1ZyXkAEKh7Z.jpg.

-

i2.

↑

Port of Vancouver. New Brighton Park Shoreline. https://www.portvancouver.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/NBP-2018.05.16-0407-1024x767.jpg.

-

i3.

↑

Figure 1. Neherlands News. (2013). Arcadis to design sediment diversion from Mississippi to Louisiana coastal wetlands. https://www.dutchwatersector.com/news/arcadis-to-design-sediment-diversion-from-mississippi-to-louisiana-coastal-wetlands

-

i4.

↑

Figure 2. Urban Omnibus. (2010). The Staten Island Bluebelt: Storm Sewers, Wetlands, Waterwayshttps://urbanomnibus.net/2010/12/the-staten-island-bluebelt-storm-sewers-wetlands-waterways/

-

i5.

↑

Figure 3. Port of Vancouver. (2020). New Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Project. https://www.portvancouver.com/new-brighton-park-shoreline-habitat-restoration-project/

-

i6.

↑

Figure 4. Port of Vancouver. (2020). New Brighton Park Shoreline Habitat Restoration Project. https://www.portvancouver.com/new-brighton-park-shoreline-habitat-restoration-project/

-

i7.

↑

(a) Video https://youtu.be/H5IsENv48-I?list=PLcLNnQfI92DdSOcDZYLKlhXoGpXGlopnf